Is Your Start-up Idea Really Worth It?

How To Evaluate A New Digital Product Business

You’re in love with your idea, but love is blind. I’m here to provide a friendly slap around the face and to tell you what everyone else is afraid to, before the honeymoon is over and you find yourself slumped on the sofa watching box sets and eating ice-cream straight from the tub, alone.

I often get asked the same questions by people who are working on their first start-up. The questions usually centre around how to get funding or how to develop an MVP, and the process of answering them usually involves me finding out about their business model, the hypotheses they need to test, and what else they have done to validate their assumptions so far.

It never fails to amaze me how keen people are to jump into the expensive undertaking of developing an MVP without having done the research and planning that will save them from some very expensive mistakes along the way. You need a plan, even when you know it’s going to change.

In this article I’m going to break down the repeatable process that I use to evaluate and develop a strategy for a new start-up, and I’m going to try to do it without using too much tech industry jargon in order to make it more accessible for those of you who haven’t been through this before.

I’m also going to provide a worked example of a digital product business from concept through to MVP stage, along with various resources that you can use for your own business. In essence, these are all the steps you need to go through before you get to thinking about raising investment.

The Idea

Pick something that you know and care about. When a TV exec tells me they have a brilliant idea for a disruptive fintech business, I get worried. Ignore what is popular — you might think it’s easier to get investment for something that is the flavour of the month, but everybody else is thinking the same thing, and they’re wrong.

Even if your fintech idea is really good, be honest about whether you’re the right person to do it. Do you have a deep understanding of the problem you’re trying to solve and do you care about the people you’re solving it for? Do you have the right skills and experience? If not then:

- It’s easy for someone to come along and do it better than you can. Always a risk, but not insurmountable if you’re genuinely into what you’re doing and willing to work harder and smarter than anyone else.

- After a few years, the novelty will wear off and you might find yourself deeply invested in working on something that you don’t really care about. It’s already over, but sunk cost fallacy will make you drag it out.

Let’s start developing an idea. I’m going to pick something related to my first love — music. As well as playing piano and guitar, I like to collect vinyl records. I wouldn’t call it an obsession, but I’ve been doing it since I was a teenager. This makes for a good foundation — I understand the space and my interest in it has already passed the test of time.

What problems are there with collecting vinyl records that I could solve with a digital product? At this point, I decide to get in the bath and think through recent vinyl purchase journeys, almost all of which were online, not allowing myself to get out until I had at least two useful insights. These turned out to be:

- There is a disconnect between where I discover music (e.g. Spotify, radio, friends) and where I purchase it (e.g. Amazon, Juno Records etc.). It’s expensive to buy vinyl, so I tend to only buy things that I really like and will want to play again and again. There is nothing right now that prompts me to buy things that I’ve been listening to recently.

- I will usually have to check in a couple of different stores before I can find what I want. If the record is available in multiple stores, there can be a lot of price variance - I’ve seen 50% price differences. This only really applies to new vinyl — for second hand we already have the discogs.com marketplace.

Bathing will solve a lot of your problems

The Proposition

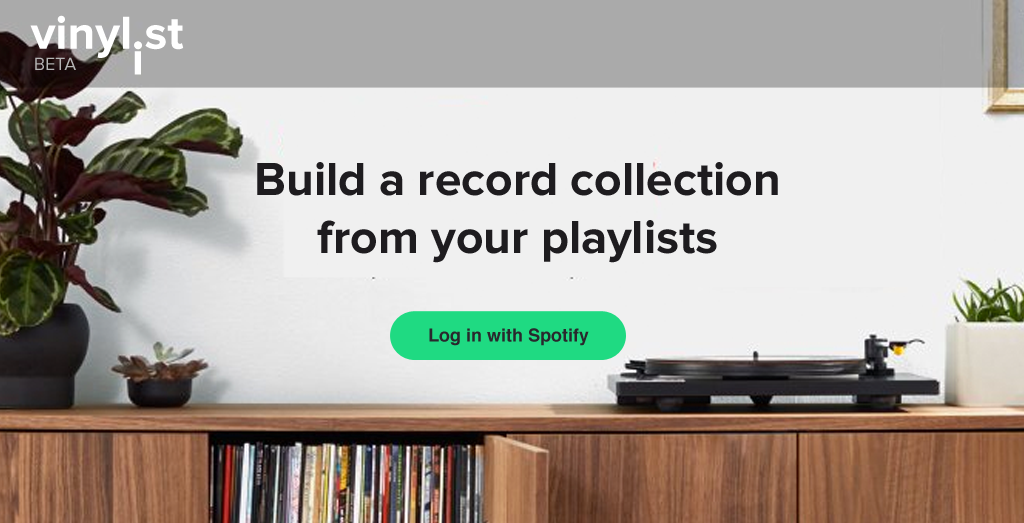

In response to these problems, we need to propose a solution. I propose an app that:

- Acts as a price comparison service and aggregates results from all online vinyl retailers. It should simplify the buying process by removing several duplicate search steps, and presenting the best option for combination purchases, where you’re buying multiple records and if you can get them from the same seller you can often save a lot on postage.

- Integrates with the places where I’m discovering and saving music that I like — in my case Spotify playlists, but could also be other streaming services, Shazam, or even recommendations from friends on social. It should be able to make smart recommendations for albums I want to buy based on what I’m listening to.

- Provide regular reminders, via email for example, to buy music that I’ve been listening to a lot recently on vinyl.

Ok, this all sounds pretty good, and if you’re anything like me you’ll be champing at the bit to get on with making an MVP. Sure, the ultimate test will always be whether we can get people to actually pay for our product, and in order to validate that we will need to build it. But wait! There’s a lot more we can and should figure out first.

Must resist building anything yet, but the odd sketch won’t hurt

The Lo-Fi Business Model Canvas

So called because what I do here is based on Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas, but I like to keep it lo-fi and work entirely in a single text file, Evernote, or even a physical notebook. This stops me from getting distracted with presentation and allows me to spew out thoughts with minimal inhibition. It also means I can be fairly loose in the format and change the questions that need to be asked based on the business I’m working on. This is all about planning out the business on paper, and allowing the concept to develop along the way, while it’s still cheap to change direction.

Turn off your phone, and give yourself a few hours to write down everything you can think of in response to these questions:

- Revenue Streams — What are the different ways in which your idea could make money?

- Market — What do you know about the potential users of your product. Is there an established market / sector already, if so what are the segments, demographics, how big is it and how much of it could we capture?

- Customer Acquisition — What would we need to do to get customers? If our business is B2C will we need to do lots of advertising or paid search to make people aware of our product? Is it an option to partner with companies who already have the customers? What sort of marketing strategies would be applicable?

- Competition — How are people solving this problem right now? Are there direct competitors or indirect competitors? How do we differentiate ourselves and maintain an advantage?

- Risks — What assumptions have you made? There are probably a lot more than you think — for instance you’re assuming that the problem you’re addressing really exists, and that people will pay to solve it. List all the things that could happen to wipe your business out.

- Pivots — Think about other angles and related ideas. How might the tech you’ve made be repurposed? Even for a completely different industry. You might think it’s too early to think of this now but it’s an important creative exercise to go through that might change your core proposition.

Here’s a snippet of what this looks like for our vinyl record aggregator idea:

Note that at the end there is a section entitled Research Required. For everything that you don’t already know or that a quick Google can’t reveal, just note it here for now. This section should always contain some interviews with your customers, partners and suppliers — you can learn a lot just from talking to people. This section should also contain things you can do to test your hypotheses without building a product, and actions you can take to mitigate the risks you’ve identified.

Do the Research

You now have a nice fat list of things you need to find out in order to assess whether your idea can work, and effectively de-risk any further endeavour.

Go and talk to people. Tell everyone about the idea, ignore them when they tell you it’s a great idea, but listen to what they say and take note of whether it is easy for them to grasp — if they are in your target market and find it hard to understand then that means something. Now go and talk to potential customers, suppliers and partners — share with them what you’ve found out so far, why should they help you if you’re not going to help them?

Don’t worry about people stealing an idea. If it’s original, you will have to ram it down their throats.

- Howard H. Aiken

In the case of our idea, I went and talked to several people who ran small independent record labels — from a one-man band, to a niche premium jazz label with a turnover of around £300k, to the biggest indie label in the UK.

I then commissioned a piece of research on online vinyl price variance on Upwork— it cost me £30 for someone to compile prices from the top 7 UK retailers for a cross-section of 50 albums that I chose. Doing the subsequent analysis took just a few hours, and found that the price of a new LP varies on average by 20% , and sometimes as much as 55%— validating one of our core hypotheses.

Next I needed to do some wider market research, and one of the simplest ways to achieve this is with the online survey tool PollFish. I created a custom survey of 15 questions, and asked 150 people, costing $150. You only pay for people who pass your qualifying question — so you can target a very specific audience if you want. To target our potential customers, I asked how many pieces of vinyl you bought in the last year, and only qualified the user to take the survey if their answer to this question was 1 or more.

From this survey I was able to validate two more of our hypotheses:

- Most people track the music they are about to buy on vinyl in a digital format that we could monitor to provide recommendations.

- Most people are already checking with multiple retailers when purchasing online.

Validating our hypotheses with market research on PollFish

Read up on how to avoid biasing responses with the question wording, or structure of the survey. It’s really important that you consider this carefully if you are to infer anything from the responses to your survey.

It’s always a good idea to ask some open ended questions, you never know what you’ll find out. I asked people “What is the biggest problem you face when buying vinyl online” and a significant number of people responded with issues relating to delivery time and managing returns. Things that seem obvious in retrospect, but to which I had not previously given much thought.

Running the Numbers

By now you should know something about the size of your total addressable market and you should have an idea of how much revenue you can make. The flip-side of this is how much money you need to spend (on product development, and marketing for example) in order to realise this revenue. Here’s a financial model Google Spreadsheet that is a good template for most SaaS-type businesses. If you haven’t done costed out projects like this before, you will need help from someone who has.

If it’s your first SaaS / recurring revenue business then you need to get acquainted with the basics of SaaS accounting. Perhaps the most important headline metrics are your cost of acquiring a customer (CAC) and customer lifetime value (LTV).

As a rule of thumb, your LTV should be > 3x CAC for B2B products, and >1.5x CAC for B2C.

Recognise that businesses which need to acquire millions of customers before they can become profitable are very risky and require significant capital to get anywhere near success. They usually have to monopolise their sector and grow incredibly fast. If you’re looking at one of these, face this fact sooner rather than later and ask yourself seriously if this is the sort of business you want.

For our vinyl product, we first looked at an affiliate model, where we would use existing retailers to fulfil orders and they would pay us a percentage of the retail price. In order to calculate our CAC and LTV we might make some assumptions like this:

- The average customer buys 5 LPs through our site per year

- The average LP price is £20

- The average affiliate scheme pays 7%

- Our customers are loyal and because we continually improve the vinyl buying experience, they stay with us for at least 3 years.

So the customer LTV is: 3 years x 5 LPs x £20 x 7% = £21

If we want this model to work we need CAC to be £14 (LTV/1.5) or less.

Those of you who are already familiar with SaaS finance will no doubt find this example to be grossly oversimplified, however these sorts of calculations work fine as an initial pass to see if a model has any chance of working.

Time to Kill?

Walt Disney used to be famous for (along with anti-semitism) having three rooms that he would move people between throughout the creative process. First in the “dreamer” room everyone was encouraged to express all ideas freely, the wackier the better. Then, in the “realist” room, the ideas would be developed into something that’s actually possible, and the constraints would be understood. Finally, in the “critic” room, those ideas would be coldly evaluated and most would be killed.

Now that you’ve done your research and looked at the finances, you need to move to the third room and take a cold, hard look at things with a critical perspective. Have your initial hypotheses been supported, do the numbers stack up, is this still the right business for you? If your proposition has developed, go back and check that it actually addresses the problems you identified — it’s easy for a proposition to develop quite logically into something that nobody actually needs while navigating your way through this slalom.

Have you noticed the main flaw with our toy product yet? While our research managed to validate several of our hypotheses, the numbers don’t look good. The initial idea we had of a simple affiliate business model doesn’t seem to be attractive enough if we were to believe the total market size for vinyl sales to be $350M/year. If we were able to drive 1% of those sales through our platform, our revenue would be 7% of the retail price — just $245k!

We might try to adapt our model in response to this. From interviews with labels we found that 35–50% of the retail price goes to the distributer and retailer. What if we created a platform where we allowed smaller labels to sell direct to consumer, bypassing the existing retail and distribution channels? At this point we need to cycle back through the process. It’s perfectly normal to have to revise your business model and other aspects of your strategy many times over in response to what you learn along the way.

Craft your Pitch

For some people this step may seem a bit premature, but as you might have noticed I’m really hammering home this point about figuring things out before you jump into the MVP. The output of this phase will be a simple pitch deck that you can use to convince other people that you’ve got it all worked out, you can even start showing it to investors to get feedback.

You’re now going to be selling your idea to others, aiming to get them onboard as partners, co-founders, or early employees. It’s a good idea to develop a basic brand at this point, don’t go nuts but do write a brand brief and come up with a name and workmark / logo — get someone else to do this if you’re not a designer.

Check out this guide on what you should include in a pitch deck. It can be done in a number of different ways but make sure it contains at least the information in the example below, and try to tell a story. You need to condense all that research down into the most salient points and present your proposition as strongly as possible.

- What is the problem?

- What is the solution?

- What is the market?

- How do we make money?

- Why are you the right team to back and why is now the right time?

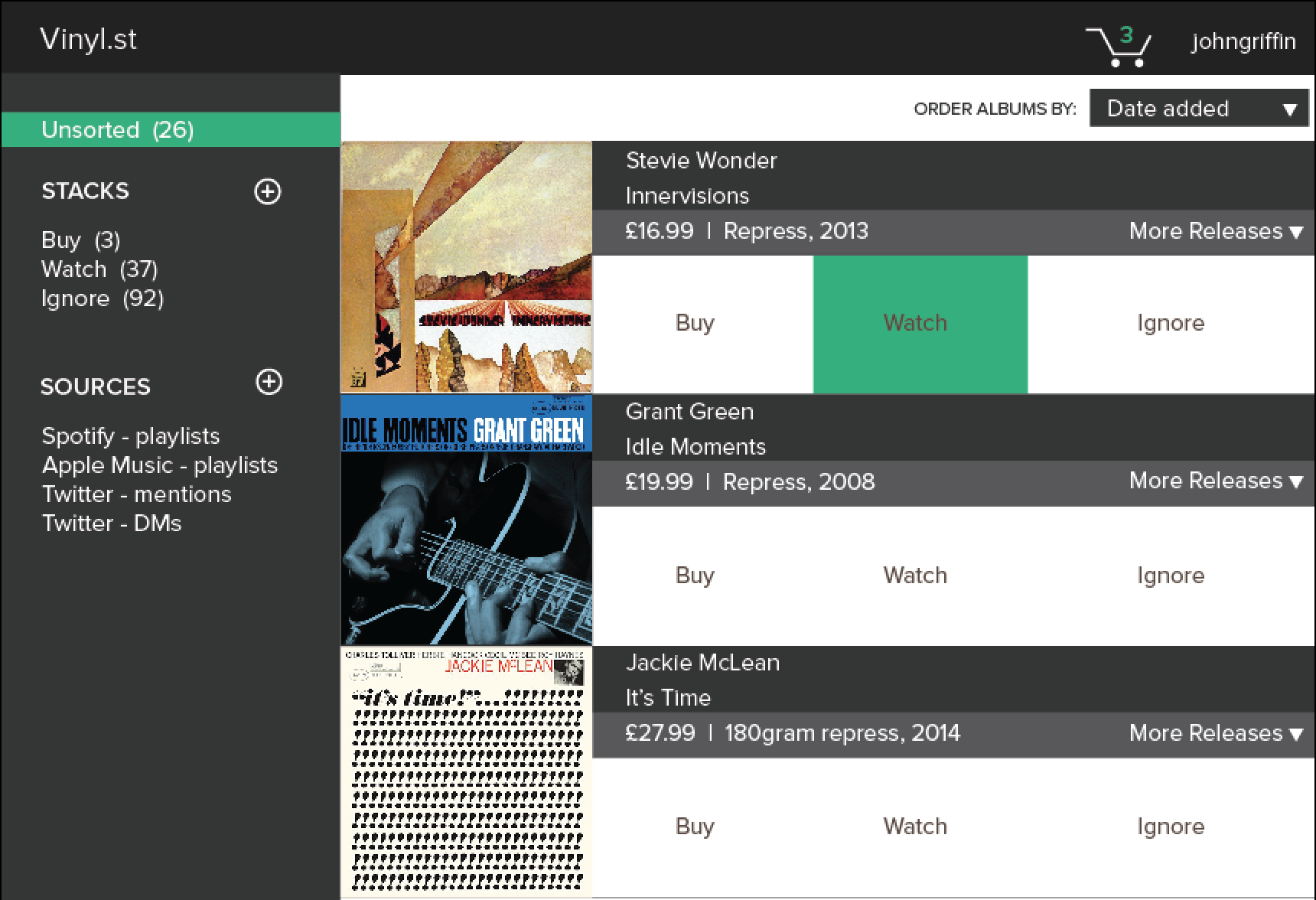

Here’s a simple 9-slide pitch deck for our idea — I’ve dubbed it Vinyl.st.

Can We Make Something Now?

Yes, but first be clear on the hypothesis you want to test, e.g:

- People buy vinyl based on what’s in their playlists.

- We can remove significant pain points from the buying process.

- We can make you buy more vinyl than you normally would.

- We can acquire and retain customers with this basic service.

Then ask: What do we need to build in order to test these? In this case it might be an app where you log in with Spotify, it mines your playlists and looks for LPs that contain the tracks from the most popular online retailers, presenting you with the best price. It will then email you each week with deals on albums you’re likely to buy, or which you have almost bought in the past and have subsequently dropped in price.

We can ask people how much vinyl they normally buy when they sign up, and then see if our email recommendation system can improve on this. The best learning comes from actual user behaviour; be sure to rig your app with customer behaviour analytics tools in order to collect this data.

There is a real art to deciding what to build for an MVP. It’s important to have some technical research going on throughout the entire process outlined in this article. You need to make sure that what you’re proposing is technically possible, and be creative in adapting your proposition based on opportunities that new technology presents.

If you get this far, congratulations! Atchai specialises in creating smart, modern web applications and we can act as an interim CTO for you, helping you to develop your product, while you raise investment and recruit a permanent team.

If you’re ready to take your product to the next level then feel free to get in touch with me directly.